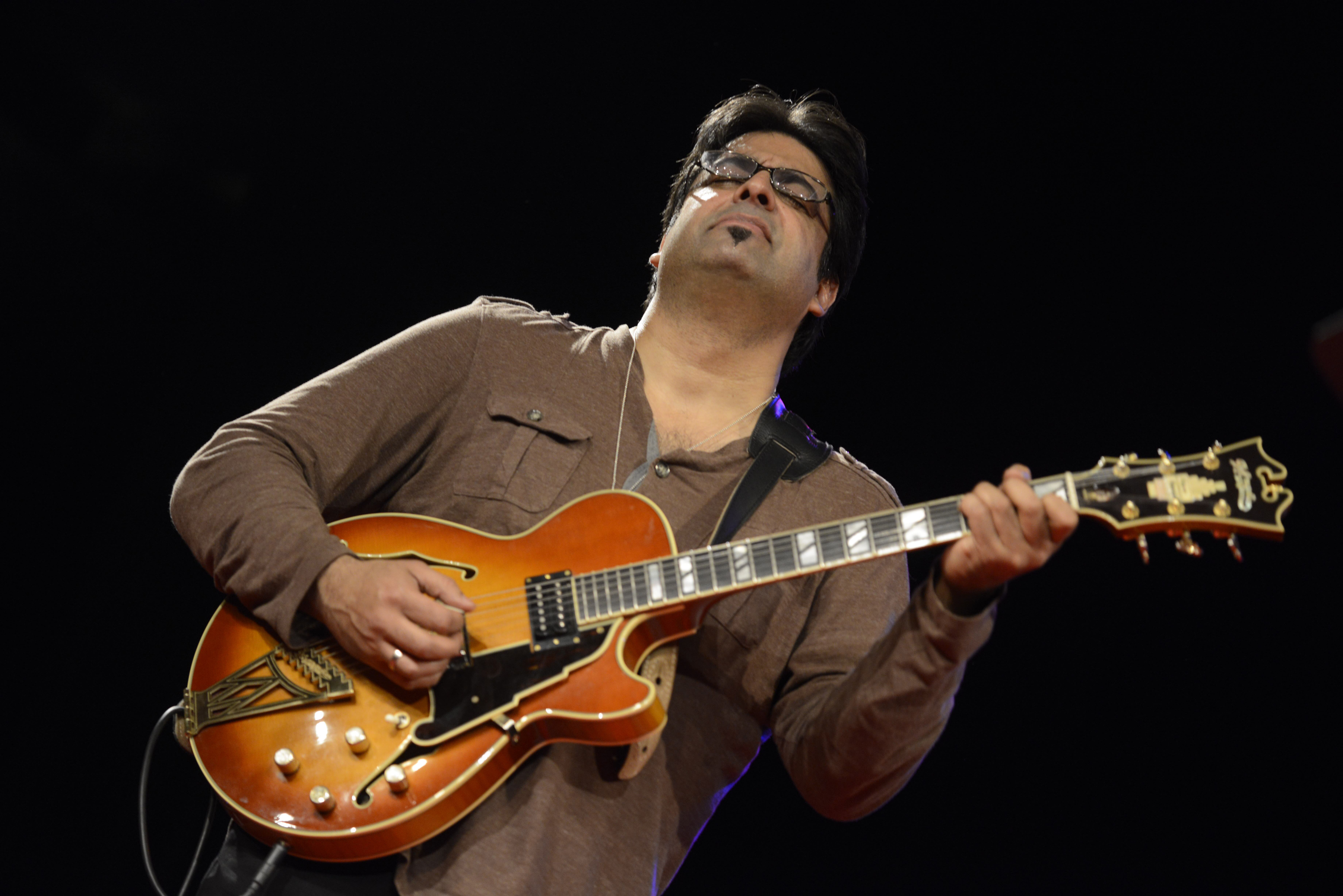

Prolific jazz guitarist Rez Abbasi has undertaken countless projects in the last 25 years, from original compositions to re-imaginings of classic works. His latest album, Django-shift, features nine songs written or made popular by Belgian-born, Romani-French jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt. While Abbasi takes these songs on as inspiration and source material, he nevertheless lends them his own style and influences, making them his own.

Hayat spoke with Abbasi about this latest project Django-shift, his work on the score for the 1929 silent film A Throw of Dice, and more.

Let’s jump into talking about Django-shift. This project was originally a commission of sorts for a festival, right?

It was Peter Williams from Freight and Salvage, in Berkeley California. He does this Django Reinhardt Festival. He asked me to do it, and at first I thought ‘wow, you know I don’t do anything like that.’ I mean I love that Django Reinhardt style, but it’s all couched in a certain kind of fabric that I didn’t grow up with. It’s not really me, per sé. So he asked me to do that, and then I remembered: wait a minute, Peter has hired me for many things, he loves my music, my original stuff…I don’t think [he’d] be asking me this if he thought I was just going to go up there and play in the same stylistic manner. So I asked if he’d be okay if [adapting the music to my own style] is only way I really feel good about it. And he said “oh, absolutely.”

So it just went from one thing to the next and what I discovered with Django Reinhardt is that he wasn’t simply an unbelievable guitarist, he was also great composer, very prolific. So then the first level was just to listen to it as is, and see what really just moved me, through the heart. And so most of it did, but there were definitely certain ones did more than others. So from there I re-listened to that new list and then I brought it down to nine tunes, two of which were not actually his, but that he covered amazingly well. And I so I figured if I was going to put all this time into it, if I was so inspired by it, why not keep it as a larger project, instead of just the one-off? It was a great learning opportunity to get into something that was very historic in nature, that I would not have probably tackled honestly. It’s something that was a great opportunity in that sense to really open my ears to a different Zeitgeist, a different history, a different world completely in the 1930s and ‘40s and ‘50s.

And that’s coming off the heels of another very unique project – A Throw of Dice. Very different projects, of course, but they both have that element of a very unique and historic origin.

I’ve definitely gotten lucky the last few years because, usually artists come up with our own ideas, and I always have and I always will, but these were kind of given to me like – because A Throw of Dice was also commissioned. And to do a film score from 1929, India – from a German director but all in India, based on the Mahabharata, the Sanskrit poem – was very lucky also. That was another thing I probably wouldn’t have done, but with these ideas are all very great.

A Throw of Dice is a 74 minute silent film, and what I learned about the process was that in my own music, in like my jazz music and records you can take 10 seconds off. You can you can put silence in there no problem, you can stop the band for 10 seconds, come back in and it’s fine. But with a silent film, you do that and it sounds like something’s wrong. There’s just so much action going on, people are moving so much. And I can relate to India, especially because I’m from that area – well, Pakistan. So the characters themselves and the plot brought out all kinds of music, but also the scenery. Because it was all India, and I miss India. Here I am in New York, and I’m looking at all this stuff from 1929 India which I’ve never seen. I’ve seen obviously modern Bombay, Mumbai now, but it’s a very different take on India.

Do you have any projects going on now, or on the horizon?

I’m not really working on something right now because of Covid, but there actually was another record that I am very proud of that’s in between those two records. It’s called Oasis and it’s with Isabelle Olivier, a wonderful harpist. It’s acoustic guitar and harp with some electronics, and tabla, the Indian instrument, and a drum set. We’ve performed a number of times and the records came out really different. I’m happy to say the results came out really beautifully.

I’ll definitely be giving that a listen. So, in addition to the guitar, you actually play tabla, and a number of instruments, right?

Well…no, actually. When I was younger, I had just graduated college and was kind of twiddling my thumbs, trying to figure out what to do, but at the same time had this yearning to go explore Indian music more. I had already had a teacher prior to that from Los Angeles, and I had all these connections to Alla Rakha – he’s Zakir Hussain’s father, Ravi Shankar’s tabla player, and really the top-of-the-line inventor of many things tabla. So I had these connections to go study with him, and I went there for two months but it wasn’t really formal study. It was enough to heighten my level of awareness of what tabla is and how it’s taught. I definitely studied it but I didn’t pursue it so much. But you know there’s clapping too, you don’t actually have to play the tabla to get into that rhythmical school if you will. And playing with a lot of people like Rudresh Mahantappa, who a lot of people know…and a few others. And my wife, in fact, Kiran Ahluwalia. Playing with that all these people who do know the tradition a little bit more than I do, it bled into me and was kind of baked into me somehow.

Less formal study, but certainly still absorbing those influences.

Exactly, and it will come out in some of my composition, just maybe not so directly. And I like it that way.

Yeah, I love it that way! I definitely wanted to talk a bit about those influences of yours. A lot of people consider you a kind of fusion artist between East and West, but I’m actually really interested in some of your even earlier influences. You started out not with jazz, but as a rock musician, right?

Yeah, when I was young, like 16 years old I was really into rock and roll. Everybody listened to very similar things back then: Led Zeppelin, Van Halen, Rush was a really big one for me. I actually played a lot of Rush in my band. That was that was really great for me at 16, and then one of my friends who was also a rocker came to me and said he was starting to study jazz and classical. And I never even thought of that. Then he introduced me to Charlie Parker and took me to an Ella Fitzgerald concert, with guitarist Joe Pass, and needless to say it was very different than rock but I knew there was some structure much more intricate, complex, and yet carrying the same amount of emotion. Although some of it sounded a little corny to me at that time, I was 16, but I knew there was something there and I knew that I could study that. I couldn’t really study rock anymore, I was really good at that time and playing dinner parties and stuff, and I felt I’d kind of graduated that school to some degree – not that I couldn’t get much better, of course. And at that point, you’re basically graduating high school, 16/17, so what am I going to do with this? Am I going to pursue being a rock star? Of course not. As a Pakistani guy, and my parents…they were thinking “oh my god, we’re too lenient with this kid…” They still say that, but of course they’re very proud now, lenient in other ways. So at 16 I said okay, look, I want to go to college for this. So I quit my rock band, started taking piano lessons, I would have a practice agenda of 6 hours a day. And my parents saw this, my mom said it was like an overnight shift, she could not believe it – her kid was this surfer, partier, rock and roller and now he’s sitting home practicing classical guitar and jazz guitar and not going outside of the house, and his friends are calling him a nerd.

Listen to the full Django-shift album here.